In conversation with James Hendry about his award-winning novel

Author of the bestselling A Year in the Wild and Back to the Bush, James Hendry talks to us about writing his award-winning novel, Reggie & Me. The importance of finding the right story, tackling writer's block and books he would recommend to a stranger.

James Hendry is currently a wildlife television presenter, who has hosted the prime-time TV series safariLIVE for Nat Geo Wild, the SABC and international internet audiences. He has worked as a guide, ranger, teacher, ecologist, lodge manager, researcher and entertainer. James has a Masters in Development Studies and speaks IsiZulu and XiTsonga conversationally.

Here, author of the bestselling A Year in the Wild and Back to the Bush talks to us about writing Reggie & Me, winner of the 2021 National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences Award in the Fiction Best Single Authored category.

This book is very different from your previous works- what prompted you to write this story now?

The original idea was to write a non-fiction - look at privilege, race and gender in South Africa. An attempt to make a contribution to de-polarising the South African society. For various reasons, this morphed into the fictional tale that is Reggie and Me. I hope some of the messages I hoped to convey in the non-fiction work will come out in this one.

You describe the harshness of a boy in an all-boys school, do you think this model of toxic masculinity so prevalent then, has changed for the better now?

I think this is a complex and massively important question. South African society of just every kind that I have experienced (including all boys schools, South African universities, rural African villages, rural Afrikaans societies, middle class white South Africa) demonstrate various aspects of male privilege, patriarchy, misogyny and homophobia, which I think is strongly linked to the toxic masculinity illustrated by bullying in all boys schools. In some cases, I think that men and boys are becoming more aware of how harmful some ‘traditional’ practices are (hazing, initiations and etc.) and some groups remain stubbornly unwilling to change. I taught at an all boys school, 20 years after I left it and there is no question that it was less tolerant of bullies and more tolerant of difference (race and sexual-orientation) than when I was there as a pupil. That said, the very public experiences of black pupils in all boys schools and private conversations with young gay men, tell me that while there has been some progress, we are still a deeply conservative society and we have a very very long way to go to becoming an inclusive and tolerant society. That said, I must emphasise that certainly where I was at school (and where Hamish is schooled!), there was very little tolerance for bullying, no corporal punishment.

Hamish spends a night in the Ntunjwas home - in the narrative how much did this impact him or was it simply a glimpse into another world and then left behind?

This visit was a glimpse into another world that Hamish takes to heart. It affects his life profoundly at various stages as he grows up. It is the first real glimpse he gets of his stark privilege and he is more or less aware of it from then on. That said, it makes him uncomfortable – to the extent that he does not try and repeat the experience. Hamish is not socially adventurous, largely because he has little self-confidence unless on stage and this means he becomes very tied up in himself which again contributes to his inability to repeat his visit to the Ntunjwas.

Hamish is very much the outsider, always trying to prove himself to a society he challenged - does this mirror your own experience at that age?

Yes it does – I mean Hamish is not dissimilar to me. Hamish’s (and my own!) struggles socially were often of his own making. He is intolerant and very tactless a lot of the time. In his defence, he really struggled to fit in socially because he lacked the intuition to fit in with any group.

Writing humour is difficult and you achieve it flawlessly. Was this difficult or does it come easily?

I don’t think it comes too easily – the greatest compliment anyone can give me about my writing is that it has made them laugh so it is very much a prime objective in my writing. I think using humour is an engaging way of communicating serious topics; it makes audiences want more rather than making them tired. This is probably what makes Trevor Noah such a massively effective social commentator.

What connects you to the characters?

Well, they are loosely based on my family so it wasn’t hard to connect to them.

Are there any lessons you hope your readers will take away from the book?

Yes, for sure but I don’t want to prescribe what those lessons are. When I started the book as a non-fiction work, I had some very specific things to say about race, privilege and gender in South Africa. Initial drafts of this book rather shoved those lessons in the reader’s face. Through excellent editing and suggestions from Pan Macmillan (the publisher specifically), the narrative was left to itself and the reader must take what they will from it. That said, I hope that white South Africans will see the far-reaching consequences of privilege or a lack thereof. I hope that black South Africans will find a seed of resonance with Hamish’s difficulties that is familiar in some way. I hope that men in South Africa will perhaps think about their attitudes to each other, women and homosexuality. Mostly, I hope readers will have a laugh, shed a small tear and leave the book a little happier than when they started it.

One would wonder, when do you get the time to write and where do you write?

This did take five years! So I don’t find a lot of time. I wrote most of this between the Sabi-Sands game reserve and my parents home in the little seaside village of Kenton-on-Sea when I was on leave from work.

How do you tackle writers block?

Yoh, that’s a tough one. Writer’s block should perhaps be generalised to ‘artist’s block’ or ‘creative block’ - visual artists and musicians also get it. Sometimes leaving the work for a while helps but often not. Sometimes just pushing through and writing a load of garbage that you know won’t make it, loosens the creative shackles. I also sometimes read funny scripts – like Blackadder or Fawlty Towers. You can (and probably should) steal small tidbits of style from the masters.

In all spheres of your work you tell stories. How important is it to find the right story?

I am not sure how to answer this one. Sometimes the substance of the story is important and sometimes it’s the way of telling the story that captivates the audience. In my work, you can tell a story about a single piece of herbivore dung that can reveal the awesome complexity of nature with a range of astonishing facts. At the same time you can tell a story about the same piece of dung that aims to make people laugh. It’s all in the telling.

On a lighter note…

If you are not writing, taking photos or recording music – what do you get up to?

I like to exercise for at least 40 minutes a day. Talk to family. Read books. Drink good coffee. Drink good scotch. Watch rugby. Swim in the sea.

What would you describe as the perfect safari experience?

A trip to the Masai Mara to witness the wonder of the Wildebeest Migration (ideally with not too many tourists to share it with). It is an experience of nature’s abundance that beggars belief and hopefully inspires a love and respect for nature that will translate to more conscious living.

What gives you the greatest joy or inspires you?

Spending time with my family. Making people laugh.

James reading list…

Five books you would recommend to a stranger

- Behave – Robert Sopalsky

- Guns Germs and Steel – Jared Diamond

- McCarthy’s Bar – Pete McCarthy

- Last Chance to See – Douglas Adams

- The Red Queen – Matt Ridley

The book you wish you had written?

Last Chance to See – Douglas Adams

What is your favourite childhood book?

Winnie the Pooh.

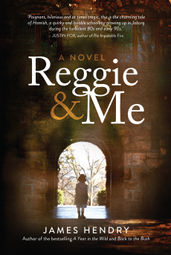

Reggie and Me

by James Hendry

South Africa – 1976 to 1994.

A time of turbulence as the struggle against apartheid reaches its zenith, pushing South Africa to the brink. But for a one small boy in the leafy northern suburbs of Johannesburg ... his beloved housekeeper is serving fish fingers for lunch.

This is the tale of Hamish Charles Sutherland Fraser – chorister, horse rider, schoolboy actor and, in his dreams, 1st XV rugby star and young ladies’ delight. A boy who loves climbing trees in the spring and a girl named Reggie. An odd child growing up in a conflicted, scary, beautiful society. A young South African who hasn’t learnt the rules.